Executive Summary

Parkland Health (Parkland) is our community’s public health care delivery system for Dallas county, Texas and one of the largest safety net entities in the USA. Parkland is a foundation for a healthy Dallas county with a population of 2.6 million citizens and 909 square miles, making it the second most populous county in Texas and ninth largest city in the United States.

Parkland, in partnership and coordination with Dallas County Health & Humans Services (DCHHS), and other community-based organizations (CBOs), has leveraged information technology and associated collected data as powerful tools for enabling improved care for those we serve. Selected technology and data-driven solutions included: 1) A Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA) that highlighted specific at-risk geographies and prevalence of disease that needed the most attention; 2) Proximity, Vulnerability, and SocioNeeds indexes; 3) COVID-19 contact tracing survey tools linked back to inform the above noted indexes; 4) Equitable vaccine distribution; 5) Electronic case reporting using CDC and AIMS platforms; and 6) Situational Awareness Network for Emergencies (SANER) public health reporting solutions. The CHNA served as a rally point for healthcare digitally transformation across a variety of channels serving Dallas county. Additionally, our community’s coronavirus response was enhanced through electronic case reporting and FHIR data exchange connecting our EMR with state and federal agencies. In collaboration with the Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation (PCCIii) and Dallas County Health and Human Services, Parkland implemented semi-automated contact tracing using text message questionnaires to positive cases and their close contacts.

Results: Multiple collaborations codified through formal Memorandums of Understanding (MOU’s) and Business Associate Agreements (BAA’s) empowered by a strong foundation of digital initiatives and data sharing have created a digitally responsive environment where Parkland and other stakeholders can act independently, collaborate, and partner to deliver data informed care for the Dallas County population we serve. For example, Parkland’s Proximity Initiatives have helped screen over 1.2 million encounters and 230,000 unique patients for risk of COVID entering the health system. Our predictive model identified patients at high risk of having been exposed to COVID with 18% of patients flagged as high risk exhibiting COVID-like illness symptoms and 26% admitting they had close contact with a positive COVID-19 individual. Over 70% of patients in Dallas County who have tested COVID-19 positive have received and begun a smartphone-based survey. Testing showed 24% of those identified as having a high Proximity Index score who were tested for COVID-19 were found to test positive. As a result of the ability to muster powerful and insightful data sources, resulting contact tracing solutions and vulnerability indexes enabled more equitable distribution of vaccines and targeted care for those with the highest risk.

The common theme across these efforts has been Parkland’s ability to integrate with and leverage flexible, repeatable, and impactful data-informed solutions in combination with regional public health partnerships, enabling improved care for Dallas County citizens. This cluster of collaborative and coordinated public health practice efforts enable Parkland to achieve its mission to advance wellness, relieve suffering, and develop and educate the communities we serve.

Define the Public Health Problem

Parkland Health has teamed with several Community-Based Organizations (CBOs) to help improve access to care for residents living in areas with the highest morbidity and mortality rates identified in the 2019 Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA). The CHNA identified significant health disparities in Southern Dallas County and documented the incidence of diseases across racial and ethnic minorities, socio-economic factors, underserved populations, and their access to care. To orient you to our population, the county’s median household income in 2017 was $53,626. Dallas tops the list for “worst connection” rate among major cities based on the Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2016 and represents the highest national percentiles for Area Deprivation Index (ADI). This needs assessment, based on public health practice and principles resulted in a set of digitally enabled programs and capabilities, which have a created a foundation for data-informed healthcare partnerships to flourish.

Carmelita Vazquez, 48, of Hutchins is one of many individuals who’ve taken advantage of these services. “We feel very blessed to have come across the social media post that led us to these services,” said Vazquez. “At the time of our visit, we were new to the area and unemployed due to COVID.”

Vazquez and her husband Roberto visited Inspired Vision Compassion Center in April of 2021 where Roberto was immediately scheduled for a follow up appointment with a Parkland provider after noticing his blood pressure was high. “The doctor we were referred to urged us to visit the Emergency Department because everything indicated my husband was close to having a heart attack,” said Vazquez. “Days later we were in Parkland’s ER. My husband was in need of heart surgery.”

Teresita Oaks, Director of Community Health Programs at Parkland says these are the types of scenarios Parkland hopes to avoid by bringing these services to the community. “These organizations are located in [specifically selected] neighborhoods where people normally gather. They include food banks, churches and social services organizations,” said Oaks. “They’re trusted by residents and bring much needed health screenings and insurance coverage assessments that will help lead them to healthier lives.”

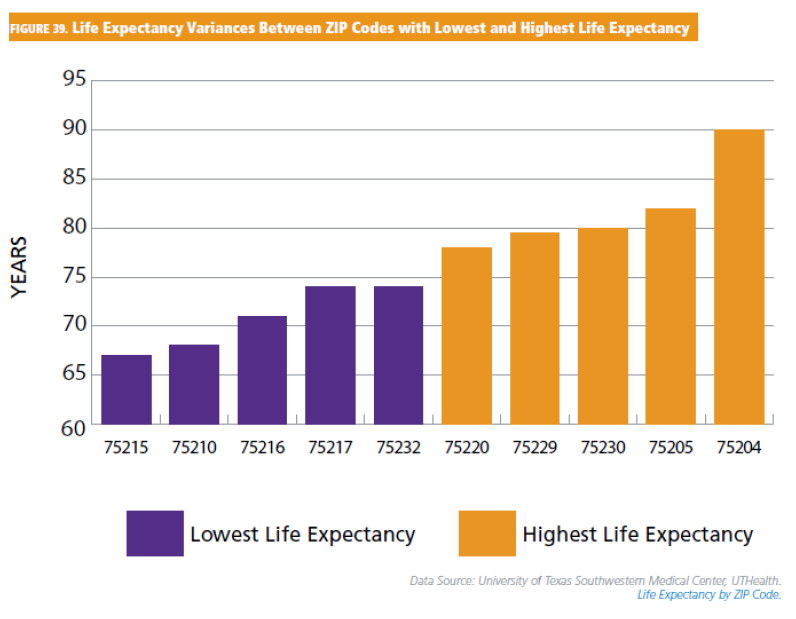

Figure 1: Life Expectancy Variances

Source: University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, UTHealth

- The uninsured rate in Texas is 1.75 times the national rate and Dallas County’s uninsured rate of 77.9% for noninstitutionalized residents is even below that of the state.

- The shortage of primary care physicians is expected to grow in Dallas County by 90% between 2017 and 2030

- In Dallas County, African Americans have the highest age-adjusted cancer mortality rate

- There is over a 25-year difference in life expectancy depending on which zip code a resident resides within

- There may be over an 8-year difference in life expectancy for residents within a single zip code between African American men and all populations.

- 15% of Dallas County residents are smokers.

Dallas County recognizes that significant disparities exist among its population and the geography of these disparities is readily apparentiii. A data informed review as part of a 2019 joint Community Health Needs Assessmentiv (CHNA) conducted in partnership between Parkland and DCHHS in adherence to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) identified several key findings:

- Access to Care – There is a high uninsured rate and a high volume of uninsured hospital discharges, particularly in the Parkland area. Dallas County has one of the highest uninsured rates among urban counties in the nation. Dallas county does not have enough behavioral health capacity.

- Health Disparities – Significant disparities by race and ethnicity and by geographic location exist within the county. Southeast Dallas county experiences the highest burden of disease and mortality.

- Special Populations – Demand for elderly and homeless health services continues to grow. Accessing health status for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender individuals remains a challenge.

- Chronic Conditions – Heart disease, cancer, diabetes andasthma, , which are related to tobacco use, poor nutrition and lack of physical activity are the leading causes of morbidity and high contributors to inpatient hospitalizations.

- Infections Disease – The increasing number of Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) cases is a significant problem.

Challenges included identifying the most at-risk citizens (patients) and providing access to care in an environment (such as a community center, mobile “clinic”, library, etc…) and manner (on-demand walk-in, scheduled, tele-visit, virtual, etc…) that met their needs, with the goal of creating a treatment plan and supportive actions that yield positive patient outcomes.

Bringing together the distinctive strengths of population-level public health with patient-level individual care, two “programmatic systems” that have traditionally operated in different spaces amplifies the impact of each on improving health. Core public health functions and principles of collecting and analyzing data, contact tracing, outbreak investigation, immunizations, isolation, and quarantine, social determinant, as well as social services support, are aligned and complementary with clinical health care in protecting and improving health. The need for integration of these two programmatic systems has emerged as critically important during the COVID-19 pandemicv and is demonstrated in the results shared below.

Design and Implementation Model Practices and Governance

Dallas County government, Parkland Health, Dallas County Health and Human Services, and other third-party Community Based Organizations (CBOs) lead multiple efforts representing a synergy of partnerships as well as self-driven organizational initiatives that cumulatively advance critical and complimentary partnerships, technology uses, and data resources. These foundational components, partnerships, technology and data, were built, shared and leveraged across multiple projects. This resulted in expansion of a valuable data set, partners able to access a variety of resources and talent they otherwise would not have line of sight into and promoted a decision-making framework that was data informed and outcomes focused.

For example, in responding to COVID-19 Parkland and DCHHS focused on shared data using ZIP Codes with a high SocioNeeds Index (elaborated on below) to provide early childhood intervention; social services support; improved access to healthy foods, physical activity, and tobacco-free environments; concentrated clinical activities; targeted employee recruitment, hiring, and development; and community investment with procurement using local vendors. Strategies also include ongoing analysis of community and public health data to inform coordinated public health and clinical service interventions.

Execution and implementation of this CHNA included government entities, Parkland, non -profits, and a broad array of community-based organizations. The parkland and DCHHS Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) and Business Associate Agreement ( BAA) outlines the collaboration between both organizations. Parkland has similar MOUs with PCCI (advanced analytics and data management skills) and multiple other external CBO stakeholders to enable data sharing (the most important element of these relationships), internet access, behavioral health services, and related referral processes. The MOU’s are the foundation of working relationships between the health providers of this community, complementing the organizations' goals, commitments, and boundaries for partnering and making a difference. The first and most powerful step in advancing similar success is creating a dialog between organizations that results in a collaborative MOU/BAA.

The CHNA program was managed through an Access to Care & Coveragevi (ATCC) initiative with an ongoing goal of identifying racial and ethnic minority populations that experience the most significant health disparities and to increase access points for health services and medical coverage in Dallas County. The CHNA assessment was funded by Parkland and DCHHS through direct and indirect means these funding mechanisms are outlined in the MOU between organizations. The ATCC is funded through a joint effort describing specific activities each organization is addressing along with detailed budgets.

The oversight framework of this initiative was directed through a Governance Committee, Core Team, and Workgroup. This framework serves as a standard tool for scalability and expansion, allowing the health system to introduce new services to the community while keeping aligned with other partners and programs.

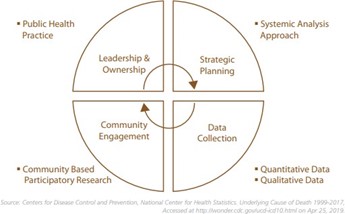

Figure 2: About Underlying Cause of Death, 1999-2017

Source: Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics

The Governance Committee included senior and C- Suite level physician, nurse and operational executives who assigned responsibilities, provide strategic direction, allocate resources, and monitor implementation status.

The Core Team included project leads who oversee all aspects of the Access to Care & Coverage Initiative structure and design, coordinate with stakeholders, ensure the completion of tasks, monitor timelines, budget, and scope.

The Workgroup staff supported development of the Access to Care & Coverage initiative clinical guidance and Community Health Worker training.

Certain projects such as the vulnerability index, electronic case reporting, SANER integration, and contract tracing were managed by Parkland leadership through internal organizational governance, often as a direct response to COVID-19 pandemic needs and prioritized alongside other hospital operations activities. Parkland worked on its own when appropriate and partnerships were leveraged with critical data sharing and technology support when that was the proper solution. There are additional opportunities to further establish relationships with programs such as Community Connect to expand EMR access to organizations that might not otherwise be able to afford or maintain advanced EMR solutions and integrations.

Leveraging partnerships grounded in MOUs enables a multiplier effect between healthcare providers and community-based organizations who share a common mission with Parkland and DCHHS.

Information and Technology Solutions and Workflow

Parkland’s ability to integrate with and leverage flexible, repeatable, and impactful data informed solutions in combination with regional public health partnerships has been critical to digitally transforming healthcare delivery in Dallas county. This cluster of collaborative and coordinated public health practice efforts includes:

- Enabling a Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA) launched jointly between Parkland and Dallas County Health & Human Services (DCHHS) through a collaborative process including the exchange of data, information, and insights

- Creating Proximity, Vulnerability, and SocioNeeds Indexes against our specific population leveraging Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) used to identify target areas for testing, education, and equitable distribution of vaccines and care

- Supporting Contact Tracing in collaboration with Dallas County Health & Human Services (DCHHS) to inform those in high-risk areas of exposure risks and to leverage survey tools to manage population risk, track symptoms and assess population health

- Focusing efforts for Equitable Vaccine Distribution, combining patient data and community health SMS smartphone surveys to identify those most at risk and create mass ticketing and scheduling push to the most vulnerable

- Supporting Electronic Case Reporting using CDC connected AIMS platform for automated sharing health data from the facility to local, regional, state, and national government agencies

- Leveraging the Situational Awareness Network for Emergencies (SANER) Project to simplify public health reporting for hospitals through shared interoperability standards based on HL7® Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR)®

Community Health Needs Assessment

In 2019, PHHS and DCHHS jointly completed a CHNA that detailed several health -related inequities with poorer outcomes among residents in several south and southeastern Dallas ZIP Codes. PCCI supported the CHNA by analyzing data such as income, education, employment, and housing status to develop a SocioNeeds Index (SNI) that correlated with poorer health outcomes and that defined areas of the county in greatest need of intervention.

Parkland and our community partners secured a variety of data from multiple sources, including internal, external, and national to create a data foundation for these collective efforts to address not only specific disease burdens, but also the root causes of the inequities brought to light from the 2019 CHNA effort. Primary data sources included:

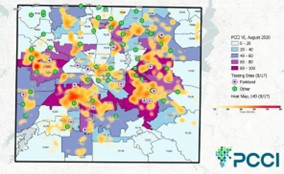

Figure 3: Heat Map of Active COVID-19. Diagnosed Cases Overlaying Identified COVID-19 Vulnerable Area Across Dallas County, Texas, August 2020

Source: PCCI

- Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System (BRFSS)

- Dallas County Health and Human Services

- Dallas-Fort Worth Hospital Council Foundation (DFWHC)

- DFWHC Healthy North Texas

- HOMES Uniform Data System (UDS) Annual Report, 2016–2018

- HRSA UDS Maps

- IBM Watson/Truven Health Analytics

- Metro Dallas Homeless Alliance

- Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation (PCCI)

- Parkland Health & Hospital System

- Texas Demographic Center

- Texas Department of State Health Services

- The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

- S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- United States Census Bureau

These data were collectively transformed into actionable insights and used to drive operational activities, such as selecting the best locations of CHNA HUB centers for providing care to patients in their communities where they are most comfortable, helping track the spread of COVID-19 and COVID-19 risks for specific communities, and ensuring the most vulnerable populations were given equitable access to vaccines.

Proximity Initiatives

Using an electronic feed of all positive COVID-19 cases from Dallas County Health and Human Services, Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation (PCCI) developed a machine-learning algorithm with geo-mapping and hot spotting technology to generate a dynamic personal risk score — a Proximity Index — based on an individual’s proximity to other confirmed, active COVID-19 cases.

Additionally, PCCI created a Vulnerability Index (VI) balanced known persistent risk factors (defined by age, condition, comorbidity, and social determinants of health) with ongoing dynamic risk factors (reduction of mobility and existing case density). Testing sites listed were open to the public or available through Dallas County Hospital District/Health and Human Services. Setting up or moving new test sites has associated costs and tradeoffs; identifying areas with high expectation of testing need/COVID-19 risk ensured testing strategy effectiveness.

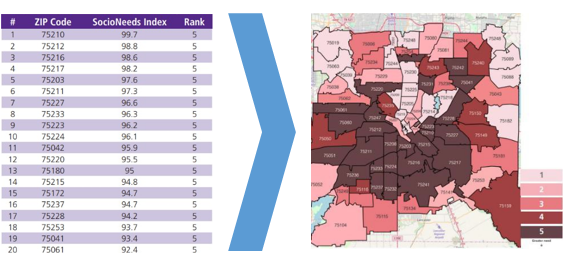

Figure 4: SocioNeedsvii Index

Source: [ ]

(SNI) score to identify zip codes that offer the greatest challenges and opportunities for addressing health disparities. SNI is a measure of socio- economic need based on ZIP Code data and is calculated from 6 indicators: poverty, income, unemployment, occupation, education, and language.

The indicators are weighted to maximize the correlation of the index with premature death rates and preventable hospitalization rates. Zip codes are given an index score ranging from 0 (lowest need) to 100 (highest need) which is then ranked from 1 (lowest need) to 5 (highest need). The darkest area in the Dallas County (SNI) map viii reveals an expansive geographic area with high socio-economic need and where health disparities are more likely to be present. SocioNeeds Index also shows the remarkable inequity between different neighborhoods in Dallas County, with the southern region being predominantly served by Parkland.

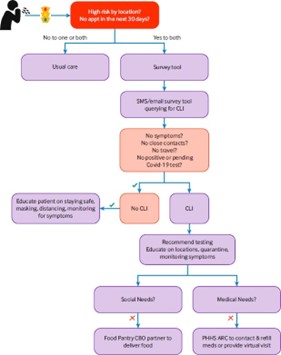

Contact Tracing

Tracking contacts of individuals newly diagnosed with COVID-19 has been a challenge across the nation and in Dallas as well. Early in the pandemic, test results were returning so late (more than a week lag) that contact tracing was ineffective. As the number of new cases identified rose to more than 1,000 per day in June 2020, the volume of tracing became impractical. Parkland informaticists worked with the county health department to create and deploy semiautomated a contact tracing solution using a commercial survey platform. This includes automated text and email messages to every new COVID-19 case (with valid cell phone or email information) within 24 hours of DCHHS’s receipt of the report, with a link to a self-administered survey, where additional information including identification of close contacts is reported. Those close contacts are then sent an automated text that includes a link to a document instructing them in isolation and symptom monitoring, as well as information about testing locations. All data obtained via the surveys are sent to DCHHS and its contact tracers for more expansive tracing activities. This solution expedites the crucial tasks of notifying and educating COVID-19–positive patients, capturing information to learn where they acquired the disease, identifying and instructing close contacts, and identifying food or housing needs.

Figure 5: Automated System

Source: [ ]

The semiautomated bilingual survey activity began on June 22, 2020, more than 3 months after the first COVID-19 cases were detected in Dallas County. As of January 21, 2021, the survey had been sent to more than 158,000 newly diagnosed individuals, 75% of all COVID-19–positive cases diagnosed in the county. Of those who received a survey, 62% opened the survey and 47% completed the survey (which represents 35% of all cases in the county). The contact tracing surveys allows for use of the same semiautomated solution to immediately notify their close contacts so they may isolate and monitor symptoms and obtain testing where indicated. Of close contacts identified, 40% have viewed the DCHHS website information regarding close contact instructions.

New COVID-19–positive cases are reporting an average of 4.4 close contacts per survey completed, and we had received more than 18,000 email addresses and 5,500 phone numbers for close contacts as of early November 2020. The survey has provided value in helping to notify and educate COVID-19–positive persons and close contacts; it has also provided valuable information regarding comorbidities and reported infection locations, which feeds into the geomapping and hot-spotting activities. Finally, Parkland and DCHHS are using the information provided regarding food or housing insecurity to address those needs.

Equitable Vaccine Distribution

Figure 6: Dallas County Race/Ethnicity Makeup

Source: 2021 Census

When COVID-19 vaccines became available in December of 2020, Parkland knew it would be critical to ensure equitable distribution to its patients. While there were specific recommendations as to who should receive the vaccinations initially (e.g., patients meeting the “1B” criteria), Parkland prioritized patients with high Vulnerability Index scores. Using a multi-modal approach, Parkland engaged patients using text messages, messaging through their electronic patient portal, interactive voice response (IVR) systems that patients could call, and via manual outbound calls from its Call Center via a work queue of the same prioritized patients. Eligible patients would also receive a “ticket to schedule”, allowing them to self-schedule their vaccine visit at a site of their preference through the online patient portal. Patients could schedule vaccine appointments through their PCP offices or through the IVR line. Parkland’s community outreach teams worked with CBOs and community thought leaders to advertise and educate about the vaccine value and availability in their community. Local health fairs were scheduled to schedule eligible patients and Parkland’s Community Health Workers scoured their local neighborhoods to educate, inform, and address any concerns.

Figure 7: SNI 4 or 5 Zip Codes

Source: [ ]

Dallas County, working collaboratively with the PCCI team, began prioritizing patients similarly, based on vulnerability. PCCI also helped inform city and county leaders regarding locations for future vaccine distribution sites using a combination of their vulnerability risk scores, geo-mapping and hot spotting of current cases, Area Deprivation Index (ADI), and data from the vaccine registration database to help identify the most at-risk and vulnerable populations with lowest vaccination rates. By February of 2022, over 77% of COVID- 19 vaccinations administered by Parkland had gone to minority individuals, and at rates that matched or surpassed the Dallas County minority population based on census data.

Over 50% of individuals vaccinated by Parkland lived in neighborhoods with the highest SocioNeeds Index scores (representing the highest socioeconomic needs). As of March 28, 2022, Parkland has administered over 390,000 COVID-19 vaccinations to the community.

Electronic Case Reporting (eCR)

Parkland was one of the first organizations in Texas to leverage APHL Informatics Messaging Services (AIMS)ix for the sharing and electronic case reporting of COVID-19 related data. AIMS is a secure, cloud-based platform that accelerates the implementation of health messaging by providing shared services to aid in the visualization, interoperability, security, and hosting of electronic data.

The AIMS platform is designed for serving public health, hosting applications and creating the ability to visualize and share data efficiently. The platform is now the default solution for public health in the 21st century. Bringing together federal agencies, the United States Uniformed Services, regional commercial laboratories and hospitals, State Health Information Exchanges and 50 state public health jurisdictions, this platform is critical public health data hub allowing…

- Aggregated Influenza test result data from public health laboratories to CDC

- Vaccine-preventable disease reports from testing centers of excellence to CDC

- Biological threat data from laboratories within the Laboratory Response Network to CDC

- Immunization data exchange among several public health jurisdictions

- Electronic laboratory reporting (ELR) between eligible hospitals and their respective jurisdictions

- National Quest ELR data to all jurisdictions

- Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) through the Advanced Molecular Detection (AMD) program

- Electronic Case Reporting (eCR) between providers and jurisdictions across the US

Routing messages through the AIMS services greatly enhance the users’ ability to manage data exchange routes and trading partners; once a trading partner is on AIMS, they can send and receive with any trading partner already on the Platform with minimal effort rather than maintaining multiple connections to a variety of senders and pollers. In addition, the translation and transformation services that AIMS offers make it easier for agencies and laboratories to exchange data with a variety of senders and receivers.

Situational Awareness Network for Emergencies (SANER) Project

The Situational Awareness Network for Emergenciesx (SANER) Project to simplify public health reporting for hospitals through shared interoperability standards based on HL7® Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR)®. The SANER Project helps health systems and public health officials across the state of Texas find information on hospital admissions, capacity, and other information critical to responding to health emergencies, including the COVID-19 pandemic. The SANER Project is an open-source effort to streamline and accelerate real-time transmission of de-identified data among health care facilities, critical infrastructure, and governmental response authorities during public health emergencies and disasters.

The SANER Project leverages a standards-based approach to ensure apples-to-apples exchange of health care situational awareness data during disasters and public health emergencies. Through application programming interfaces (APIs) using HL7® Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR®), an international data sharing standard, essential elements of information can be automatically extracted from several data sources within a hospital. Data sources may include the electronic health record (EHR), bed management system, asset management system, and inventory control. Data elements include number and status of specific hospital bed types, availability of staffing, and the number of ventilators and other critical supplies. These data may be shared with other hospitals, local, state, and federal public health authorities, and relevant response organizations.

The Texas Health Services Authority (THSA), HASA (a health information exchange in Texas covering multiple regions), and Audacious Inquiry received funding from the U.S. Departmen t of Health and Human Services’ Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) focused on increasing data sharing between jurisdictional Immunization Information Systems (IISs) and Health Information Exchanges (HIEs)

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) awarded federal funding to THSA under the Strengthening the Technical Advancement and Readiness of Public Health via Health Information Exchange (STAR HIE Program) to develop the SANER Project in Texas. The STAR HIE Program aims to strengthen existing state and local HIE infrastructure so that public health agencies may better access, share, and use health information as well as support communities that have been disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Impact on Public Health

While the loosely coordinated health care market does not lend itself well to the command -and control structure required for managing a large-scale disaster, individual health systems can prepare for and respond to a disaster in different ways that will prove beneficial during a crisis. Establishing formal partnerships with local public health departments and community organizations before a crisis will establish the working relationships and trust necessary to move quickly with support in the face of an ongoing disaster. There are numerous examples of health systems partnering with public and community-based organizations that can be leveraged in the time of a crisis.

Public health institutes are partnerships of government agencies including health departments, health care delivery systems, foundations, and other community organizations with missions directed at improving population health. One such entity, the Colorado Health Institute, developed a Social Distancing Index — a tool that uses measures of overcrowded housing, population density, and essential job prevalence to describe census tract risk scores used to inform governmental policy in response to COVID-19.

A growing number of health systems have adopted anchor institution missions through which they commit to focus resources on addressing historic inequities and improving the overall physical, mental, and economic health of the communities they serve. This involves structured partnerships with government and community-based organizations to achieve outcomes including more and better jobs, support for local business, education support, volunteer activities, and more.

Some direct outcomes resulting from the CHNA efforts include:

- 5 community-based hubs with Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) operating in 6 locations were created to facilitate addressing key findings on location

- 14 community health workers sourced from target zip codes were hired to conduct screenings and education

- Community screening data is now captured using an Epic-based workflow, allowing further insight into citizen needs and profiles

- Hundreds of patients have been seen and thousands of screenings have occurred

It is notable that the PHHS/DCHHS experience has had its shortcomings. The large-scale testing was hampered by prolonged test turnaround time for the first 4 months due to use of the county using a third-party vendor. Contact-tracing staffing and processes were slow to develop. Ultimately, local officials agreed to pivot from the federally supported laboratory to other contracted labs funded through county and city sources (using federal emergency funds) in order to achieve results within 48 hours. Likewise, the health department increased its staffing to support contact-tracing activities and revamped its processes and electronic platform. Still, that process continues to have gaps in its ability to reach all new positives and their contacts in a timely manner. While testing at the county jail has been key to limiting spread, that program developed more slowly than is ideal, which speaks to the complexity of coordinating a public health response within a corrections system.

Parkland can support a public health function because it is a publicly funded safety -net institution. Many areas of the country do not have that type of resource; therefore, it is even more important to establish public health connections prior to a disaster. This could be accomplished through structured agreements and could be considered part of the required CHNAs and funded, in part, through the required community benefit spending by nonprofit systems.

While one can hope that this is our “pandemic of the century,” as was the 1918 influenza pandemic for our predecessors, that would be wishful thinking; many experts predict another pandemic much sooner than the separation between the last two. xi xii Health systems generally lack a public health perspective and expertise, and local health departments lack resources and practical experience in delivery system operations. Better acquainting the two before a crisis can ease the ability to work together quickly and efficiently during a crisis.

The partnerships and integration of formal programs between Parkland, DCHHS, and multiple CBOs provides one example of how collaboration coordinated through MOUs, shared and aligned goals, and a collective vision can deliver better public health. The common theme across these efforts has been Parkland’s ability to integrate with and leverage flexible, repeatable, and impactful data- informed solutions in combination with regional public health partnerships, enabling improved care for Dallas County citizens. Proactive collaboration among major health systems and their local health departments can influence population health, progress the triple aim, and mitigate delays in the rapid deployment of the large-scale responses necessary to effectively address emerging and traditional public health threats.

Appendix

i. Parkland Health, https://www.parklandhealth.org/about-us

ii. Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation – PCCI, https://pccinnovation.org/connected-communities- of-care/

iii. Dallas County Community Health Needs Assessment 2019, https://www.parklandhealth.org/Uploads/Public/Documents/PDFs/Health-Dashboard/CHNA%202019.pdf

iv Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Community Health Assessment, https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/cha/plan.html

v. NEJM Catalyst, The Imperative for Integrating Public Health and Health Care Delivery Systems, https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0580

vi. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Access to Care, https://www.ancor.org/newsroom/news/cms-releases-request-information-%E2%80%9Caccess- coverage-and-care-medicaid-and-chip%E2%80%9D

vii. SocioNeeds Index, https://www.healthyntexas.org/indexsuite/index/healthequity

viii. CHNA 2019, pg 14, https://www.parklandhealth.org/Uploads/Public/Documents/PDFs/Health-Dashboard/CHNA%202019.pdf

ix. APHL Informatics Messaging Services offered through the Association of Public Health laboratories, https://www.aphl.org/programs/informatics/pages/aims_platform.aspx

x. Situational Awareness for Novel Epidemic Response Project (SANER PROJECT), https://thsa.org/hie- texas/saner-project/

xi. Brulliard K. The Next Pandemic Is Already Coming, Unless Humans Change How We Interact with Wildlife, Scientists Say. The Washington Post. April 3, 2020. Accessed January 13, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/science/2020/04/03/coronavirus-wildlife-environment/

xii. Murdoch D. The Next Once-a-Century Pandemic is Coming Sooner than You Think – but COVID-19 Can Help Us Get Ready. The Conversation. June 14, 2020. Accessed January 13, 2021. https://theconversation.com/the-next-once-a-century-pandemic-is-coming-sooner-than-you-think- but-covid-19-can-help-us-get-ready-139976

HIMSS Davies Awards

The HIMSS Davies Award recognizes the thoughtful application of health information and technology to substantially improve clinical care delivery, patient outcomes and population health.