The social determinants of health, also referred to as SDOH, are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age, and have gained recognition for the broad impact these conditions have on health, health equity and overall well-being. Factors include food security, socioeconomic status (income, educational attainment and subjective perception of social status), access to care, reliable transportation, safe housing, neighborhood characteristics and the composition of a person’s social support network. As outlined in Healthy People 2030, the fifth edition of a set of science-based, 10-year national objectives developed under the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the social determinants of health can be grouped into five domains:

- Economic Stability

- Education Access and Quality

- Healthcare Access and Quality

- Neighborhood and Built Environment

- Social and Community Context

The conditions included in each of these domains are shaped by a wider set of social, economic and political forces known as the structural determinants of health including public and social policies, governance, macroeconomics and societal and cultural values. These structural determinants can foster inequities associated with race, sexual orientation, class and other attributes of human difference that can produce systematic disadvantages, which lead to inequitable access to positive SDOH experiences and ultimately dictate health.

In This Guide

Relationship Between Social Care and Medical Care

Impact on Individual Health, Community Health and Population Health

Social Determinants of Health Data and Information Standardization and Use

Infrastructure Standards

Social Determinants of Health Assessment

Workflow Considerations

Cross-Sector Stakeholder Considerations

The Impact on ROI of Healthcare Systems

Equitable Access to Broadband and Technology

U.S. Policies and Initiatives

HIMSS Public Policy Principles and Considerations

Global Policies and Initiatives

Relationship Between Social Care and Medical Care

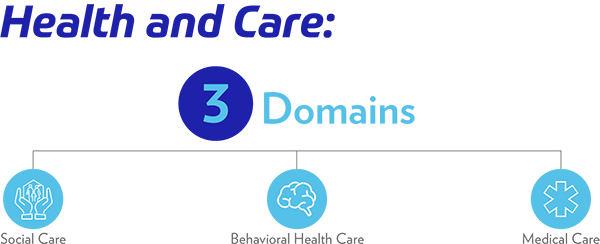

Health and care can be viewed as the sum of three domains: social care (the services that address social needs such as housing, food and transportation), behavioral health care and medical care. By using this evolved and more complete view, the myopia of the synonym of medical care and healthcare is shed, thereby explicitly including social and behavioral services as essential and perpetual parts of healthcare.

Impact on Individual Health, Community Health and Population Health

As the driver of health inequities, or the differences regarding the access individuals have to achieve optimal health, social determinants of health have shown a greater impact on population health and individual well-being than factors such as biology, behavior and medical care. Socioeconomic status—when compared with other health risk factors such as physical inactivity, diabetes, smoking, obesity, high blood pressure and high alcohol intake—is found to be one of the strongest predictors of illness and death worldwide. The sustained and stable relationship between socioeconomic status and health shows that individuals with higher socioeconomic status (including higher subjective social status assessment) consistently experience better health than those with lower socioeconomic status, and this occurs across a social gradient. Medical care, although essential for health, has shown to be a relatively weak influencer of health in that it has been estimated to account for only 10-20% of the modifiable contributors to healthy outcomes for a population. The other 80-90% have been attributed to the social, economic and environmental factors referred to as the social determinants of health.

By capturing information and data that reflects attributes of an individual’s daily life (including socioeconomic status, occupation, social support system, neighborhood characteristics, etc.), one can derive comprehensive insights into factors that influence health. In many cases, this insight is more valuable than what would be learned from traditional medical sources. This realization is accompanied by a set of technical, organizational and operational considerations that require scrutiny of such things as data standardization, technical infrastructure, workflows, cross-sector stakeholder relationships, and the return on investment (ROI) implications for health systems and other medical providers as the migration toward value-based care continues nationally.

Social Determinants of Health Data and Information Standardization and Use

Health information and technology systems capture both data (discrete elements that are representations of physical state or direct observations such as blood pressure, lab results, or heart sounds) and information (summaries of data, or semantic interpretations of data such as a diagnosis of hypertension, diabetes or tachycardia). Data and information that capture attributes of SDOH are often available in both clinical and social contexts, but the manner in which these attributes are captured will often differ across domains, as are the structure, syntax, taxonomy and transmission format. While the health information and technology in use by medical providers has undergone a sequence of standardization over the last 20 years, the tools in use by social and behavioral health service providers have not yet become standardized in the same way. Yet in order to properly identify social needs, implement interventions and measure the positive (or negative) impact of these interventions, there needs to be a way to standardize the health information and technology used in all settings, not just those in use by medical providers.

To ensure that social determinants of health data can be captured and used by all members of the community working to address these factors, the data must be captured, represented in, and exchanged using standards. The Interoperability Standards Advisory (ISA), a resource curated by the Office of the National Coordinator (ONC), exists to “coordinate the identification, assessment and determination of recognized interoperability standards and implementation specifications for industry use to fulfill specific clinical health IT interoperability needs.” When incorporating social determinants of health data it is important that the information is structured and encoded based on standard code systems and uses appropriate value sets. By doing so, the information becomes not only part of an interpretable resource, but provides the ability to have the information used by decision support tools and provides the ability to alert service providers to social risks that may change treatment decisions. The ISA does contain a section for social, psychological and behavioral data including code sets for things such as food insecurity, exposure to violence, level of education and transportation insecurity. If this represents all health-related information in terminologies such as LOINC, SNOMED, CPT, HCPCS, ICD-10, and RXnorm, then clinical systems will be able to parse and interpret it. The challenge of such a medical-centric approach is that the social and behavioral health systems currently in use in food pantries, substance use disorder treatment facilities, transportation providers and housing agencies may not speak in ontologies that the medical domain has adopted. While some of these terminologies have recently incorporated elements that represent SDOH, these efforts are nascent and have not yet fully captured the breadth of observations that will be necessary to capture and communicate social needs and interventions.

Examples of clinical terminologies include:

- LOINC typically represents observations and, where appropriate, the results of the observations (e.g., laboratory tests, vital signs; and for SDOH, housing instability).

- SNOMED-CT is used to represent medical conditions and interventions and is used primarily for health concerns, problems and diagnoses (e.g., diabetes, COPD), and services and procedures (e.g., hip replacement, immunization)

- ICD-10-CM codes typically represent the administrative equivalent of health concerns, problems and diagnoses when communicating with a healthcare insurer.

- CPT and HCPCS are used to represent services and procedures when communicating with a health plan.

- RXnorm codes are used to represent a specific medication and/or allergy to a medication.

The use of standard syntax to exchange encoded information is essential to using social determinants of health data by all members of a community-wide service team. There are several exchange standards that could support the exchange of both clinical and SDOH information. Standards in use today include various HL7 standards such as the Clinical Document Architecture (CDA) and the Consolidated Clinical Document Architecture (C-CDA) and ASC X12 standards for administrative transactions (e.g., eligibility and billing). The emergence of HL7 FHIR® has provided a new standard to communicate clinical, administrative and potentially social determinants of health information. FHIR is named as the required clinical interoperability standard in both the ONC 21st Century Cures Act Final Rule and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Interoperability Final Rule. The role of FHIR in SDOH has not yet been explicitly addressed by ONC, but it remains a viable and potentially attractive framework to be considered.

By representing social determinants of health data using clinical terminologies described above and the new FHIR standard, there is the opportunity to exchange and incorporate SDOH data in clinical systems in a manner that will provide both syntactic and semantic interoperability. Nonetheless, this needs to be careful not to assume that medical systems are the hub of a community’s wheel. There are systems in use by social and behavioral healthcare providers nationally, and these systems already use some native terminologies. As the interoperability of these systems evolves, it may be valuable to develop and maintain mapping capabilities so that clinical systems continue to use clinical standards, and social and behavioral service providers can use standards that are more familiar or usable to them, since the imposition of clinical standards on other service domains may be inappropriate.

Infrastructure Standards

As health systems continue to recognize the importance of taking these factors into account, health IT projects are requiring expanded infrastructure components to either incorporate the social determinants of health data into health information and technology or to create federated enterprise information systems that access SDOH data and aggregate it to support both treatment and public policy formation. Because the original sources of social determinants of health data components may be in multiple domains, independent standards have emerged. Today, a full implementation of SDOH in health information and technology systems would require that those systems implement different interoperability standards to interoperate with multiple domains, including FHIR, HL7v2 and C-CDA (medical care); Common Education Data Standards, Ed-Fi and Postsecondary Electronic Standards Council (education), National Information Exchange Model (justice) and other standards.

Where the capture of SDOH data is encapsulated in a medical enterprise system—so the data is managed by enterprise software—standards are still important if the inevitable aggregation of data from different systems is to serve the needs of evidence-based program and policy decisions. In this case, the system requires specific aspects of infrastructure that are recognized as best practices for data management and quality control for any quality system development. When the data about social determinants is collected from external systems (i.e., different domains such as social services, education, etc.), there are more infrastructure components that must be created or acquired.

As an example, the Gravity Project, a national public collaborative and HL7 FHIR Accelerator, is developing individual-level data standards to represent the capture and exchange of social determinants of health information in health and human services electronic systems. The work is focused both on the semantic representation of the data via nationally recognized vocabulary/terminology standards (i.e., LOINC, SNOMED-CT, ICD-10), and the structural exchange of the information using HL7 FHIR based open APIs as defined in the HL7 SDOH FHIR Implementation Guide. The Gravity Project defined terminologies are applicable across other content and transport standards including HL7v2, C-CDA, Direct, IHE Profiles, and other FHIR implementation guides. For example, the FHIR Bidirectional Services eReferrals (BSeR) Referral Request Transaction Profiles currently reference a few of these SDOH terminologies. In addition, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) documents a set of sources for SDOH information from outside the medical realm; these are less easily integrated into a medical care encounter and health information and technology system, but may be essential to accurately describe individual, family, or population health matters.

Critical to any health IT infrastructure is the capability to 1) reconcile inconsistent use of SDOH codes across different healthcare settings and 2) inconsistent implementation across health information and technology systems. Any information system needs to address these kinds of conflicts and inconsistencies from disparate domains.

The need to establish semantic interoperability requires a capability to map terms from disparate domains, with appropriate translation guides either incorporating external entity resolution components or equivalent capabilities embedded within systems. As highlighted in this EHR Intelligence article, even independent of synchronization on specific social determinants of health standards, there is the ongoing challenge of inconsistent implementation of interoperability standards across health information and technology systems. The work of various testing environments, such as MiHIN and InteroperabilityLand test environments, as well as various connectathons and ONC certification services, is critical to the long-term assurance of interoperability.

The integration of individuals’ health and SDOH data enhances the validity of information about them as it is stored in health information and technology and therefore necessitates greater attention to privacy protections. Further, such integration requires the establishment of trust across domains to allow for the efficient replication of data and information to create improved knowledge and ideally improved outcomes, which requires the rules of access at the point of origin of the data to be preserved across domain lines and applied to secondary use.

The key components of infrastructure that have additional implications are:

Authentication—Determining and validating the identity of the user accessing the system requires a federated identity-management capability that can operate across domains participating in the sharing of data and information.

Authorization—Permitting access to an integrated model of health and SDOH data implicitly necessitates role-based authorization, with the ability to limit access dependent on role constraints down to the individual data component.

Person-matching (resolution)—Matching records across domains requires a methodology to manage both semantic and syntactic variations and to resolve issues for combining data and information from multiple sources.

Consent management—Making sensitive (personal/identifying) data and information available for secondary use across domains requires a consent-management component that is domain neutral to establish informed consent.

Privacy/security constraint policy management—Cross-domain data and information sharing requires the capability to enforce rules of access or sharing limitations that conform to the policies of the originating system.

An example of a framework for introducing these components can be seen in Project Unify, a proof-of-concept effort organized by Stewards of Change Institute’s National Interoperability Collaborative. Project Unify envisions data and information being made available via application programming interfaces, irrespective of whether the data or information being manipulated is from medical care, justice, education, housing, transportation or another domain. The same is true of server-side functions that offer callable cloud-based services. The cloud-based services may be based on a serverless architecture, a container-based architecture or, for that matter, any other architecture that can provide access via an API.

Project Unify recognizes that most advanced implementations are moving toward the various cloud models, ranging from software as a service, or SaaS, to platform as a service, or PaaS. The participants in this project also have acknowledged that any useful framework must make it easy to write an application that is built by assembling pre-built components or widgets into a high-value application. The software development industry is no longer composed of monolithic coding mountains; instead, it is increasingly built of individual components, whether internally constructed or purchased. It is also true that the infrastructure must support a variety of mobile and fixed operating systems and protocols.

Federated systems with the flexibility to accommodate interoperability across multiple standards frameworks—by using components that can be dynamically reconfigured to handle variations in content—will be the hallmark of future systems that incorporate social determinants to facilitate improved individual and population health.

Social Determinants of Health Assessment

The identification, capture and communication of social needs through the use of assessment tools is becoming more common throughout multiple care domains. Social determinants of health assessment tools enable the identification of individual social risks reflecting a person’s unmet social needs. These tools, although differing in methodology, content and follow-up procedures, often focus on key social determinants of health domains. The EveryONE Project from the American Academy of Family Physicians considers five variables as core health-related social needs including housing, food, transportation, utilities, and personal safety. These five variables are included in the project’s SDOH Short-form Screening Tool. The project’s SDOH Long-form Screening Tool includes these five core health-related social needs, as well as screening questions for needs in employment, education, child care and financial strain.

There are many tools available to screen for these needs, yet there is lack of national guidance on the use and effectiveness of these tools. According to NCQA’s Social Determinants of Health Resource Guide, once an organization has made addressing SDOH a strategic priority, designing a social determinants of health assessment program involves four main work streams.

- Whom to assess: Determining whom to assess might depend on an organization’s resources, budget and current workflows. Some organizations may choose to conduct universal assessments, while others may start with high-risk individuals and expand to a broader scope once workflows are optimized.

- What to assess: Strengths-based assessment, needs-based assessment, and risk-based assessment are three different approaches to the assessment of SDOH. Strengths-based assessment is often used in behavioral health and focuses on measuring a person’s protective factors (e.g., social support system, access to resources) that help them thrive even in adversity. Risk-based assessment and needs-based assessment are more commonly used in medical environments and focus on capturing the individual characteristics that put a person at risk for poorer physical health (e.g., poverty, sexual orientation) or what an individual’s immediate unmet social needs are.

- What questions to ask: Although most readily available social determinants of health assessment tools include screening questions centered on food, housing, transportation and financial situation, there is limited evidence that supports screening for specific SDOH factors. When choosing specific questions, an organization may consider what the social risks in the population served are and the available local resources.

- How to implement the assessment: A variety of individuals may have responsibility for social determinants of health assessment including social workers, community health workers, physicians, care managers, nurses, transportation providers, clergy, housing assistance providers, health coaches, and many other service providers. Methods used for collecting the information have included verbal in-person, verbal remote, written assessment, and through the use of a kiosk, computer workstation, smartphone or tablet.

Although an organization could develop and validate its own questions, organizations often find it most expedient to implement previously developed and validated assessment questions or tools. The most widely-used tools today include the Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences, Health Related Social Needs, The Health Leads Screening Toolkit and the Health Begins Upstream Risks Screening Tool.

- Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences (PRAPARE): The PRAPARE assessment tool, developed by the National Association of Community Health Centers, consists of a set of national core measures as well as a set of optional measures for community priorities. It was informed by research, the experience of existing social risk assessments, and stakeholder engagement. It aligns with national initiatives prioritizing social determinants (e.g., Healthy People 2030), measures proposed under the next stage of Meaningful Use, clinical coding under ICD-10, and health centers’ Uniform Data System.

- Health-Related Social Needs (HRSN): CMS developed the HRSN Assessment as part of the Accountable Health Communities Model. The HRSN helps providers find out patients’ needs in five core domains including housing instability, food insecurity, transportation problems, utility help needs and interpersonal safety.

- HealthBegins: The Health Begins Upstream Risks Screening Tool was developed by HealthBegins, an organization that is focused on upstream health risks. The tool has 28 questions assessing five domains including economic stability, education, social and community context, neighborhood and physical environment, and food.

- The Health Leads Social Needs Screening Toolkit: This toolkit provides a comprehensive blueprint for organizations seeking to identify and screen individuals for adverse social determinants of health. It includes a number of updates based on the latest social needs research, lessons learned from long-standing screening programs, and feedback from front-line clinicians and healthcare providers.

While screening for and documenting the social needs of an individual may help us to better understand the broader context of their lived experience and stressors, referral mechanisms are needed to allow clinical providers and care managers to refer individuals to appropriate social services and community-based organizations that are available to meet the need. A number of electronic referral platforms and digital technologies to link people with health and social problems to community-based providers has evolved.

Social Determinants of Health Task Force

Explore the opportunities that exist in the meaningful integration of social determinants of health (SDOH) data to properly inform care delivery and improve individual and population health. Members seek to provide expert guidance to drive SDOH-related efforts in healthcare information and technology forward, specifically anchored in standardization, implementation and policy development.

Workflow Considerations

SDOH and behavioral health data may be introduced to the clinical setting through manual data collection during assessment, as patient-generated health data from patient portals or mobile health applications, or as data from a community organization. Advances in technology have the potential to improve efforts in the flow of social determinants of health data and information among all members of the healthcare team. However, to successfully integrate SDOH data into care processes and person-centered care, clinical needs and workflows must be addressed.

With the widespread implementation of health information and technology systems, there is a growing amount of evidence that suggests health information and technology systems disrupt clinicians’ workflows through increased documentation and searching for patient information without much added benefit. So much so that CMS launched the Patients Over Paperwork Initiative to create efficiencies and reduce the documentation burden of clinicians. In their report, the National Academy of Medicine found that the poor integration of health information and technology into clinical workflow affects clinician professional well-being, and recommended that clinicians be included in the design and development of health IT, including EHRs. The addition of new social determinants of health data sources using new technologies must be introduced to the clinical setting in a way that supports workflows and does not cause unnecessary work on the part of the clinician.

To facilitate the use of social determinants of health data in patient care, the following aspects of clinical workflow should be considered in the design and implementation of SDOH-related technologies.

Assessment

As part of the assessment phase, the mechanics of the SDOH data intake process should be configured in a way that requires minimal data entry by the clinician. Decisions should include how the data are collected (i.e., screening, survey, checklist), what method is used (i.e., paper, portal, tablet), which member of the care team ensures the data are collected, at what point the data are collected (i.e., before the visit, at the start of the visit, during the visit), and whether the data is visible within the health information and technology system or if the clinician must access a separate system. Integration decisions regarding the passive or active collection of social determinants of health data should be a part of the implementation planning. If an active process of pulling data into the system is required, human factor approaches should be used to ensure usability and safety of the processes. If a passive process is used, alerts should be configured to notify the provider about the presence of SDOH data in the system.

Care Planning

In order to use social determinants of health data for care coordination and social care planning, interoperable platforms with open standards should allow for the sharing of the necessary structured, actionable data to most health IT systems. The level of summarization and contextualization of the data should support and inform care interventions and be presented to the clinician at the point in the workflow that the SDOH data will meet the information needs. Social determinants of health data can be leveraged in clinical decision support algorithms and enhance predictive models to inform connections with community resources as part of discharge referral workflows. Big data strategies can be leveraged to identify social risks and needs at the population level, and potentially automate non-essential clinical tasks.

Education

As more healthcare organizations integrate social needs screening into clinical care delivery, it is vital to consider the perspectives of patients and caregivers regarding the use of SDOH data and technology to connect social services with healthcare. A growing body of research shows that by and large, most patients at a large integrated health system supported clinical social needs screening and intervention. However, new workflows may be needed to further educate and support patients on the collection of SDOH data and the use of new technology tools. This is especially important for patients that may experience embarrassment or a loss of dignity by sharing certain information. Community partners and peer champions might be required as part of the processes to smooth the transition. Similarly, clinicians may require training on new care models and redesigned workflows that incorporate social determinants of health data.

It is critical to examine workflows and engage clinicians in the introduction of SDOH data into care processes and new technologies. User-centered design and human factors approaches should be used to ensure efficiency, usability and safety. Workflows should strive to reduce the documentation burden of clinicians and improve the clinical work environment with the goal of improving patient outcomes and the care experience while addressing social and behavioral needs.

In this HIMSS TV Deep Dive, we show how health systems are leveraging advanced technologies such as AI, analytics and telehealth to manage patient populations – but are still staying focused on the basic building blocks of health and wellness.

Cross-Sector Stakeholder Considerations

Cross-sector stakeholder relationships between health systems, community-based organizations (CBOs), public health entities and other key healthcare providers are crucial in the integration and meaningful use of social determinants of health data in care delivery settings. Although often operating in separate, yet parallel worlds, there is an acknowledgement amongst these entities that greater cooperation would benefit all involved as a community’s social and built environments, economic stability, discriminatory practices and access to quality healthcare all contribute to an individual’s overall well-being. For example, large CBOs, when compared to health systems, are often better positioned to collect data on social needs as they have a greater ability to collect more nuanced, ongoing, and up-to-date information about individuals that present with social care gaps and needs. Although CBOs often lack the infrastructure and staff to participate in data sharing arrangements with health systems, these organizations, along with public health entities often maintain a multifaceted understanding of the communities in which they work and can offer health systems valuable insights as to how certain social services affect a community’s health. This dynamic partnership allows health systems to create and maintain connections with under-resourced sectors of their communities who may not be engaged in the health system at all and therefore, increase the overall health of the attributed or geographic population they serve.

The perspective of patients and community members must be considered in the design and implementation of any SDOH solution. An article in the Journal of Preventive Medicine describes the roles community members can and should play in, and an asset-based strategy for, building large-scale community health research infrastructure that serves community needs and priorities.

One example of a foundational approach to the successful partnership between a community’s clinical and social sectors is found in the Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation’s Connected Communities of Care Playbook.

Connected Communities of Care (CCC) address critical gaps between clinical care and community services in the current healthcare delivery system. A CCC consists of a technology platform, community alliances, and the governance for cross-sector data sharing, care coordination and community alignment. The CCC framework enables and supports enduring relationships across diverse stakeholders and is a way to make SDOH insights actionable, with the ultimate goal being to positively impact whole person health. This critical alignment requires cross-sector collaboration between:

- Healthcare systems and medical care providers

- Social services

- Community-based organizations

- Public health institutions

- Federal, state and local government agencies

The CCC Playbook offers insights into the crucial role of governance, how to get started in building collaboration and alignment between these necessary stakeholder groups and considerations on how to sustain a highly cohesive and well-functioning group.

Additionally, the Center for Health Care Strategies and Nonprofit Finance Fund with support from Kaiser Permanente Community Health partnered to explore the operational, financial and strategic considerations required to make partnerships between health systems and community-based organizations impactful for healthcare consumers, providers and community-based organizations. The three case studies included in this exploratory project revealed critical components of success which include building community ecosystems, managing through partnership evolution and building the case for partnership. The case studies included in this project offer information to help refine an existing partnership or guide the development of a new partnership between healthcare organizations and community partners.

The emergence of alliances amongst stakeholders across the health delivery ecosystem to better address the medical and social care needs of the population served has led to a new breed of partnerships and an expanded approach to healthcare delivery. This expanded approach, born out of the recognition of the limits of medical care in reducing socially driven health disparities, has furthered a concern around the medicalization of SDOH interventions.

Medicalization can be described as a process by which personal, behavioral and social issues are viewed through a biomedical lens, giving medical professionals the authority to diagnose and treat what are purportedly social problems. This can perpetuate the notion that health-related societal problems need a healthcare solution. It is important to remember that the overarching goal is to improve health outcomes and health equity at the societal level and harmonizing the medical and social care sectors is a continuous and evolving journey. These partnerships should be built and operate in a way that does not divert resources and policy attention away from the larger, systemic forces at play that create and perpetuate health inequities.

The Impact on ROI of Healthcare Systems

Healthcare systems core business imperatives are to scale efficient and effective care to the persons and the communities that they serve. Working on thin margins and caring for the most vulnerable persons among us, healthcare systems routinely accept government assistance and participate in other capital support programs that ensure fiscal survival in the setting of massive care needs from the uninsured or underinsured in the community. Because of this frequent market situation that healthcare systems find themselves in, most current social determinant program investments are lumped into the same charity category on the financial ledger along with cumulative unreimbursed care and aggregate community benefit dollars.

This observation has been a clear disservice strategically to healthcare systems as it has obscured their ability to see the positive financial impact of investing in and addressing the socio-clinical needs of persons and populations. Healthcare systems have not had expectations that their social determinants of health programs can provide insights and interventions that guide corporate action at scale leading directly to a business case return on investment. But it can be done, and many healthcare systems are getting in on the return. Specifically, moving their SDOH programs from a lost leader expectation, to the expense side of the ledger, to actually impacting the top-line revenue side of the business while driving strategic growth and resource allocation with greater precision.

The first steps for healthcare systems in this transition takes commitment and stamina, but a return on investment can be immediate, sustainable and grow as the market unlocks the most deterministic health factor –the social determinants of health—and the direct effect of the SDOH on the total cost of care, resource allocation, patient experience and clinical outcome. What was once only a charity expense, is now core to the business and with the impact of value-based care transition, can become a million-dollar revenue generating endeavor. Expert partners can enable healthcare system leaders to drive impact on those at greatest risk for increased utilization or bad outcomes from SDOH risks. In order to make this transition happen, certain considerations need to be made such as: (1) Where can healthcare systems find and grow this bottom-line impact of SDOH? (2) What are the operational considerations along the journey to incorporating SDOH into care delivery? (3) How can we get started with this transition to value and impact?

With any corporate change of significance, a candid self-assessment of a healthcare system from the outset is warranted. Where does the healthcare system sit on the social determinants of health maturity model? Are they interested or committed to the social determinants of health? Are they organized or scattered in their programs and interventions? Are they acting alone or with community partners to a common goal? Where on the corporate budget do these costs sit? By both expertise and research, we know most systems are on the early part of the maturity curve, and their corporate interest in SDOH exists in direct proportion to their degree of participation in value-based care. Specifically, the more healthcare systems are actively taking on financial risk to the total cost of care, the more organization, innovation and commitment rolls into the SDOH efforts.

More specifically, where can a healthcare system locate ROI with SDOH? A good starting point is in looking at the garnered ROI with better allocation of resources with SDOH precision. Follow-up phases include aligning existing programs with ROI-primed quality measures that are impacted by SDOH and then concentrating interventions on at-risk populations to launch fully risk-adjusted revenue metrics and expand covered at-risk populations. None of these are single variable endeavors, and each option are multidisciplinary strategies. The alternatives here do not need to be addressed in sequence but do need complete corporate focus as spreading business efforts too thin will dilute the ROI and be reminiscent of just a charity. Many mature healthcare entities can also measure initiatives on more specific criteria like return on outcome (better satisfaction for the individual and community), return on experience (better health value for the individual and community), and finally and poignantly return on equity (better health equity for the individual and community). With focus remaining on the dollars, it is necessary to unpack each of these pathways to unlock ROI from SDOH with further discussion and operational considerations.

Align Existing Programs with ROI-Primed Quality Measures that are Impacted by the Social Determinants of Health

Many healthcare systems participate avidly in a multitude of quality measure programs for reputational benefits, clinical excellence, and incentive payments. These quality measures vary from the former core measures, to hospital compare metrics, to Healthcare Effectiveness and Data Information Set (HEDIS) and Star Measures, to National Quality Forum (NQF) value sets, to specific Accountable Care Organization measures, and ultimately to disease specific national care guidelines and residual bundled-payment programs. Each healthcare system has too numerous to count measures, all that support relevant business cases of value. Prioritizing the quality measure inventory diligently and with a purpose to lock in on the measures with the most effect can help put SDOH work on the pathway to business ROI. Specific examples of this in play are when healthcare systems identify and quantify the SDOH risk on a single line of business or service line (i.e., cardiac care). With this analytic focus, health systems synchronize the social influencers with the programmatic and clinical drivers to attain specific quality measure objectives. Examples like annual wellness visits and use of a statin for heart disease are real examples where this has yielded a nice return for health systems. It is important to note that existing quality programs are prevalent both inside the walls and outside the walls of the healthcare system. Understanding how to partner with community social programs that advance disease outcomes and promote better early utilization (i.e., not going to the emergency department for routine care) will add further business return to this social determinants of health alignment strategy.

Lastly, rarely do these SDOH-impacted quality measure programs focus on one line of business or one service line for maximal benefit. There is real opportunity for further ROI when the level of analytics precision links the quantification of SDOH risk into subdomains (food security, housing, transportation, health literacy, etc.). This further characterization of SDOH risk on outcomes allows the healthcare system to match precise need (in a primed subpopulation) with the specific paired intervention(s). This scientific method approach creates a scenario where aligning existing programs better addresses already important quality measures yielding real business returns from existing programs involving social determinants of health interventions.

Concentrate Interventions on At-Risk Populations

On the supply side of this effort, the intervention strategies are more finite than the multitude of SDOH risk factors for communities and persons. Because of this, to improve ROI, healthcare systems can select and cultivate an organizational expertise around one or two domains—for example Financial Opportunity Centers. With executive commitment and developed expertise in the specific domain programs, the fixed costs to start and to manage an intervention program is reduced. In addition, there are greater synergies when it comes to applying the strategy in outreach in support of the subpopulation in need. To improve ROI for SDOH interventions, health systems need both upstream robust analytics to discern the precise subpopulation to cooperate with and the downstream community expertise and understanding to translate the program into one that has the characteristics of value and trust to maximize benefit for all. Concentrating on and developing mature programs that take cultural competence and racial equity into account improve the adoption, cooperation and alignment around the outcomes of better health at less cost. Healthcare systems will garner financial reward from reduced utilization in these at-risk groups, and the community will have more programs that take care of their own with socio-cultural relevance.

Launch Fully Risk-Adjusted Revenue Metrics and Expand Covered At-Risk Populations

Finally, the gold standard for ROI comes from full risk-adjusted payment models that factor the social vulnerability of the subpopulation into the capitated payment model—much like Hierarchical Condition Codes did for medical/clinical risk adjustment. In these models, many more lives and many more dollars are at stake, as these payment models favor proactive investments to reduce the total cost of care and these types of social risk adjustment form the central tenant of the value-based care movement. To reap consistent and ongoing value from programs, there must be a foundational commitment and investment in increasing the amount of value-based care in the healthcare systems portfolio. When this threshold of value-based care is achieved, and the populations in play are hundreds of thousands of individuals, economies of scale kick in for the business model.

To achieve enterprise ROI for SDOH interventions, health systems need to have the capability to apply systematically to their entire at-risk population both upstream analytics to discern the precise subpopulation in need and the downstream community engagement to translate the program into an intervention that maximizes business ROI in an ongoing replicable manner. The recurrent and consistent application of this process of quantifying SDOH risk creates a learning system that iterates on the outreach methodologies that work and refines those that don’t. This allows healthcare systems seeking ROI to improve in both process and analytics in tandem. Launching fully risk-adjusted revenue programs for large at-risk populations is not easy and should not be the first step in pursuit of ROI for healthcare systems early to the space. However, in time and with maturity, this business capability to expand programs that work (smaller ROIs) to become enterprise efforts (increased capitated payments upfront) for the system is the proverbial holy grail of social risk-adjusted return on investment.

For healthcare systems an ROI can be immediate and grow as the market unlocks the deterministic factors of SDOH. The direct effect of these factors on the total cost of care is compelling in resource allocation, patient experience and clinical outcome. With the increase of value-based care payment arrangement, SDOH strategies can generate millions in savings and revenue. Healthcare systems should have expectations that their programs can provide ROI at the outset and in the future at scale leading directly to profitable business cases. To assure ROI for SDOH interventions, health systems need both upstream robust analytics to discern the precise subpopulation to cooperate with and the downstream community expertise.

Equitable Access to Broadband and Technology

As healthcare continues to become increasingly digitized, the technological advances that pose the promise of improved care have also created the potential for negative, unintended consequences related to the social determinants of health and health equity. The proclivity of technological advances in healthcare to produce or exacerbate health inequities is increasingly being highlighted as a concern for public health. Socio-demographic characteristics and social determinants of health—particularly age, education, income, geographic location and perceived social isolation—can also predict internet access and use proficiency. Rural populations, racial or ethnic minority groups, those of low-socioeconomic status and older adults are less likely to have the digital health literacy skills, or the knowledge to use emerging information and communications technologies to improve or enable health and healthcare, and the access to internet-capable digital devices needed to engage in and benefit from virtual health services.

To avoid duplicating and further exacerbating the social stratification that exists in society-at-large within healthcare, these digital determinants of health have rightfully become an area of heavy focus. There is a current push to advance equitable access to health information and technology as telehealth, remote patient monitoring, artificial intelligence, big data analytics and the use of mobile health apps have proven potential to enhance health outcomes by improving medical diagnosis, data-based treatment decisions, digital therapeutics, self-management of care and person-centered care.

The COVID-19 Pandemic has Presented New Challenges and Increased Urgency to Address Broadband Access

The COVID-19 pandemic, given its devastating consequences on the elderly, those with chronic comorbidities and racial or ethnic minority groups, has added significant urgency to the mission of using technology as the great equalizer in healthcare. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has driven educational, professional, social, health and self-care activities and opportunities online in huge volumes; further exacerbating digital disparities. A 2020 Pew Research Center survey identified that more than half of U.S. adults (53%) say the internet has been essential during the pandemic and nearly half of low income survey respondents expressed worry about being able to pay for high-speed internet connection. These results could suggest a need to more proactively assess broadband access insecurity and affordability concerns as part of social needs screening and to connect individuals to services to support increased access. Several initiatives across federal, state and local levels have emerged to respond to the growing disparities, especially among families with children, during the pandemic.

Perhaps the most notable initiative is the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recent release of the draft global strategy on digital health 2020-2025 with the vision to improve global health by “accelerating the development and adoption of appropriate, accessible, affordable, scalable and sustainable person-centric digital health solutions to prevent, detect and respond to epidemics and pandemics, and developing infrastructure and applications that enable countries to use health data to promote health and well-being.”

U.S. Policies and Initiatives

Broadly in the United States, governmental public health and healthcare agencies have at hand an abundance of data and information to improve research, interventions and health policy decision-making that impact the determinants of health at all levels. This is especially important given state and local governments are challenged by fiscal austerity measures along with expanding population health and wellness needs due to new demands arising from health ramifications from natural disasters, the rise of resistant infectious diseases, namely, COVID-19, and other health threats such as the opioid epidemic and climate change. The imminent need to address these crises is intensified by a rapidly changing healthcare landscape. Likewise, the push towards value-based healthcare has challenged primary care to deal with population health issues such as health disparities, chronic disease prevention and community health; this has initiated a renewed interest in collaborations between public health and private healthcare agencies. Despite advances in healthcare, too many individuals will continue to needlessly fall ill unless we change the conditions that contribute to poor health. Adopting public policies that improve access to quality education, safe housing, jobs and more can have lasting effects on health outcomes. The following HIMSS policies and U.S. based initiatives advance the use of data, information science and technological advances to address health equity and improve social determinants of health.

In the U.S. the following initiatives and policies have been developed to modernize and advance health information and technology and data systems:

- Healthy People 2030 - Since 1980, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has established a set of 10-year, evidence-based national priorities and objectives called Healthy People to improve health. For this decade, Healthy People 2030 sets data-driven national objectives to improve health and well-being over the next decade. Healthy People 2030 features many objectives that would help the United States become more resilient to public health threats like COVID-19 and to leverage health IT and data systems to achieve these goals.

- With regard to health information and technology, Healthy People 2030 focuses on helping healthcare providers and patients leverage digital tools to guide the United States in improving health and well-being. The primary objectives are:

- Health IT—General

- Health Communication

- Increase the proportion of adults offered online access to their medical record—HC/HIT 06

- Increase the proportion of adults who use IT to track healthcare data or communicate with providers—HC/HIT 07

- Increase the proportion of hospitals that exchange and use outside electronic health information—HC/HIT D05

- Increase the proportion of doctors who exchange and use outside electronic health information—HC/HIT D08

- Increase the proportion of people who can view, download, and send their electronic health information—HC/HIT D09

- Increase the proportion of people who say their online medical record is easy to understand—HC/HIT D10

- Neighborhood and Built Environment

- Public Health Infrastructure

- ONC provides resources on social determinants of health and health IT

Public Health Data Modernization and Data: Elemental to Health Campaign

The CDC launched the Data Modernization Initiative (DMI), which seeks to transform methods for the collection, use and sharing of data through modern IT capabilities. The DMI proposes to address the following key questions:

- How do we improve timeliness and quality of data?

- How can we better coordinate data activities and systems?

- How can we reduce burden on data partners?

- How can we integrate emerging technologies more effectively?

In coordination with the CDC’s DMI initiative, the Data: Elemental to Health campaign, supported by a broad-based coalition of healthcare and public health organizations, aims to secure federal funding for CDC and state, local, tribal and territorial health departments. Specifically, the campaign supports building the coordinated and expanded public health surveillance capacity. The public health data infrastructure requires a seamless and interoperable framework that automatically draws information from the healthcare system and reports it to public health agencies.

The CDC has begun targeting investments across three priority areas: 1) data sharing across the ecosystem, 2) enhancing CDC services and systems for ongoing data modernization, and 3) new standards and approaches for public health reporting. By investing in these three areas, CDC is working toward a system that can be scaled nationwide and adapted as needs and technology evolve. These priority areas support core public health functions and help policymakers assure that timely, correct data can be leveraged to address health equity issues, and to enact policies and provisions that address social determinants of health.

States

Over 40 states are attempting to address SDOH by expanding partnerships for care coordination and improving state infrastructure and processes needed to address the interrelated health and social needs of their low-income populations through Medicaid managed care contracts or 1115 Waiver demonstrations. For example, the State of Indiana launched the Indiana Data Hub, one of the first of its kind in the United States. This Hub allows unprecedented public access to secure, de-identified Medicaid patient data that illuminates trends on health determinants.

A number of communities are starting to leverage their health information exchanges (HIEs) to support SDOH data sharing. For example, the city of San Diego, California has one of the most mature models of this kind, called San Diego Health Connect. Another robust example is the partnership between HASA, the Texas HIE, and Methodist Healthcare Ministries of South Texas to create a demonstration project that links SDOH data to electronic health records. This pilot’s primary goal is to provide physicians a more complete view of patient health. Similar to North Carolina’s efforts, HASA helps connect patients with a variety of community services able to reduce the need for emergency visits.

Virginia

Virginia Health Opportunity Index is Virginia’s statewide data visualization platform, consisting of 13 health indicators. It illuminates health disparities at the county, city and neighborhood level. In the city of Richmond, for example, disparities exist between neighborhoods of different races and socioeconomic status. The data show that lower health outcomes are concentrated in communities of color and that life expectancy is up to 20 years younger in communities of color compared to white, more affluent communities, just across the river. Leveraging this mapping tool to visualize outcomes sends a message and driver for intervention.

In the future, there is a hope to make this more of a predictive model to understand which factors will have the greatest impact on health. Also, the state would like to incorporate legislative districts into the map, so legislators can see how an intervention can save a certain amount of lives in their district. This is an example of how we can leverage modernized systems and data for action. However, significant challenges exist with modernization, integration and interoperability across state agencies to achieve these aspirations.

North Carolina

In North Carolina, its statewide vision and goal is “to improve the health of North Carolinians through an innovative, whole-person centered and well-coordinated system of care which addresses both medical and non-medical drivers of health…” This goal is reflected in their key healthy opportunities initiatives that leverage digital health.

One of these key initiatives is NCCARE360, the result of a public-private partnership unites healthcare and human services organizations with a shared technology platform. This allows for a coordinated, community-oriented, person-centered approach to delivering care. Stakeholders can communicate in real time, make electronic referrals, securely share information, and track outcomes together. Due to COVID-19, NCCARE360 fast-tracked their efforts across the state and now serves all 100 counties.

The program has seen improvements in a short amount of time. In August 2019, less than 10 counties were on NCCARE360 and it took about 23.6 days to close a case. A year later, in August 2020, it took about 2.9 days to close a case and the program has sustained this for four months, even during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The following is a success story due to leveraging the tool: A pregnant woman visited a local Women Infants Children (WIC) office. She was already enrolled in WIC, but she was food and housing insecure. The WIC office did not have those resources themselves, but they were able to connect her to a suitable resource through the tool. Typically, it may have taken weeks to coordinate because of a fragmented system, but the woman was connected to services and able to receive critical services in a matter of days.

California

The growing demand for transparency and control over the collection of personal information by companies, similar to the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), has sparked increased attention on data privacy and security among state governments. The 2018 California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) has recently gone into effect and is serving as a model for other states. In addition to California, Oregon is seeking to institute the Oregon Health Information Property Act which goes further by granting patients the ability to authorize their healthcare providers to sell their health data with financial compensation to the patient/consumer if their health information is sold to a third party. A growing number of states are seeking to implement legislation modeled after this law.

The CCPA ensures that businesses cannot discriminate against you for exercising your rights under the CCPA. Businesses cannot make you waive these rights, and any contract provision that says you waive these rights is unenforceable. For instance, a California resident could ask businesses to disclose any personal information collected about the individual and what they will do with the individual’s information. A resident may also request the business to delete personal information and not to sell their personal information. Under this law, an individual also has the right to be notified, before or at the point a business collects personalized information, of the types of personal information they are collecting and what they may do with that information.

States Leveraging Health Information Exchanges (HIEs)

A number of communities are starting to leverage their HIEs to support SDOH data sharing. For example, the city of San Diego, California has one of the most mature models of this kind, called San Diego Health Connect. Another robust example is the partnership between HASA, the Texas HIE, and Methodist Healthcare Ministries of South Texas to create a demonstration project that links SDOH data to electronic health records. This pilot’s primary goal is to provide physicians a more complete view of patient health. Similar to North Carolina’s efforts, HASA helps connect patients with a variety of community services able to reduce the need for emergency visits.

U.S. Congress

The U.S. Congress has recently proposed a handful of social determinants of health data-related legislation, however none have passed at this point. One example is the Social Determinants Accelerator Act 2019 (H.R. 4004), which would establish the Social Determinants Accelerator Interagency Council and provide funds for the council to 1) assist the CMS in awarding specified grants, 2) increase coordination among health and social service programs, and 3) provide program evaluation guidance and technical assistance to increase the impact of social service programs.

Further, the Maternal Health Pandemic Response Act of 2020 (S.4769) was proposed to address the unique needs of pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Part of this bill proposes a publicly available pregnancy and postpartum data portal led by CMS and CDC, updated monthly during COVID-19, collected across surveillance systems, and broken up by race and ethnicity, while adhering to privacy regulations.

HIMSS Public Policy Principles and Considerations

HIMSS Public Policy Principles on Equity and the Social Determinants of Health

1. The safe, effective, secure, and integrated application of connected health technologies must play a central role in advancing better care delivery and disease management and prevention, regardless of location, and reducing health disparities.

- Policy must recognize the unequivocal value of health technologies to deliver timely and effective response during emergency events and health crises.

- Universal access to broadband connectivity should be prioritized, as it is a critical enabler for widespread telehealth access, and additionally, economic and education factors all contributing to positive health outcomes.

- Telehealth enhances access to high-quality care for at-risk, underserved, and remotely-located populations, regardless of the patient’s location, and ultimately advances health equity.

2. Communities, patients, caregivers and providers should have equitable access to health IT tools regardless of any social or economic status, such as race, gender, education, neighborhood, or income.

3. Policy should support research and programs to pay particular attention to at-risk communities in order to advance health equity. Policy should help overcome racism and bias as structural determinants of health, leading to inequities and disproportionate morbidity and mortality risk in communities of color.

4. Policy should support ethical, non-discriminatory practices of standardizing and integrating demographic and social determinants of health data. Best practices in this area serve to leverage quality care and to more efficiently identify disparities in health outcomes.

5. Policies should account for diverse levels of technology literacy and should strive to build culturally competent literacy.

HIMSS Public Policy Considerations

The following are key HIMSS public policy considerations for considering SDOH and health equity needs through the use of cross-sector data and use of health information systems.

- Support the development of local or regional health and human services data platforms to share critical community information that can improve policy decision-making, public health research, and evidence-based interventions particularly for vulnerable populations.

- Integrate Healthy People 2030 health equity and health IT measures and coordinate with state and local governmental agencies to ensure community health improvement plans, state health IT plans/roadmaps reflect the use of modern health IT data and infrastructure needed to address SDOH and any emerging health threats.

- Convene a multi-disciplinary, state-led work group to develop recommendations on how information and technology can ensure a health information and technology in all policies approach, address social determinants of health and increase health equity.

- Support funding and modernization of your state’s public health data infrastructure to expand utilization of mapping software and other epidemiological tools to identify communities with highest needs and determine appropriate intervention and support secure data sharing between social and healthcare entities.

- Support innovation and use of secure mobile applications and SMS platforms to enable a healthier, safer lifestyle.

- Support state and regional HIEs to build connections to social care networks in order to create a statewide digital platform that enhances care coordination across the spectrum of care and informs public and private SDOH goals.

- Encourage community-based, cross-sector integration by leveraging telehealth and broadband programs as a mechanism to tackle social determinants of health.

Global Policies and Initiatives

Estonia

Estonia has a national unique person identifier used across many sectors, which has helped immensely with interoperability, finding new insights in research, and clinical and social care. Regardless of the sector, information is connected by a singular interoperable data exchange platform called X-Road. The platform saves over 800 years of working time annually for the Estonian population.

Estonia has established a Youth Guarantee Information System to identify at-risk youth. The system screens at the municipality level for risk factors and includes a data lookup in registries of education, vocation, training and child support. Through this information system, program leads identify and contact at-risk youth and connect them with case workers to ultimately connect them to work, education, or training opportunities. Due to its success, this program is currently in law and is an annual process.

New Zealand

New Zealand has stood up what may be a global model for addressing SDOH. The New Zealand Wellbeing Budget focuses on improving the quality of their citizen’s lives by addressing five priorities. One of those priorities is “supporting a thriving nation in the digital age through innovation, social and economic opportunities.” New Zealand’s efforts offer a growing model to watch given possible applicability across a number of municipalities.

Updated May 13, 2021