By Toria Shaw Morawski, MSW, TIGER Initiative Liaison, Senior Manager, Professional Development, HIMSS

According to Yuri Quintana, PhD, of Harvard University, global health informatics “is a growing multidisciplinary field that combines research methods and applications of technology to improve [global] healthcare systems and outcomes.” This multidisciplinary field focuses on competency and curricula development in the benefit of education reform, fostering interprofessional community development, and gaining workforce development inroads.

This guide aims to acquaint those learning about the field with a direct conduit on where to locate and how to leverage the tools and resources available. We hope you will find this information to be of value and that you will disseminate what you discover and learn throughout the global healthcare ecosystem. Together, may we always strive to “foster a learning community of diverse stakeholders that embrace shared values to drive innovation and technology regardless of where one is located.”

In This Guide

Understanding Health Informatics Core Competencies

Aligning Core Health Informatics Competencies

Workforce Development

Understanding Health Informatics Core Competencies

By Johannes Thye, MA, Faculty of Business Management and Social Sciences, University of Applied Sciences Osnabrück, Germany; Consortium member of the EU*US eHealth Work Project

The term core competence is a rather vague concept that should be classified. Core competencies can be understood as a broadly specialised system of skills, abilities or knowledge necessary to achieve a specific goal. Core competencies also include behaviour that includes emotional, social and cognitive aspects. It is evident that it is not only about knowledge, but also about abilities, skills and behaviour. Ultimately, it is a combination of cognitive, motivational, moral and social skills that align to fulfil requirements, solve tasks and problems or achieve goals through the necessary knowledge and actions.

With regard to health informatics, these core competencies are not simply the transfer of knowledge about the use of a specific application, but rather the development of knowledge in order to use information technology (IT) sensibly and to give IT a meaning. In healthcare, there are also specific core competencies related to medical or nursing activities. Furthermore, the treatment of patients is interprofessional, in this sense, informatics core competencies in healthcare basically cover different disciplines and professions. Thus, health IT is interprofessional by nature and must be reflected in education and training. Especially core competencies such as communication and leadership are of great importance for successful interprofessional cooperation.

What Kind of Core Competencies Exist?

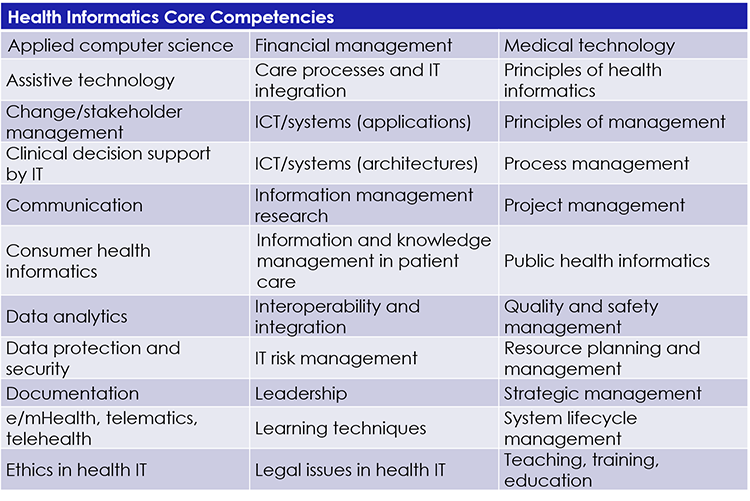

Core competencies can be divided into different domains such as IT principles, ethical and legal issues, systems life cycle management, medical technology or management. These can be subdivided into a technology, application or management focus, and the addition of interpersonal skills can also be derived. In a more detailed subdivision of management, the core competences of the individual areas such as strategic management, project management or the principles of management thus derived. Furthermore, core competencies can also be defined according to different levels, such as the Bloom taxonomy. The following table shows in summary the health informatics core competencies developed and derived for the TIGER International Competency Synthesis Project’s Recommendation Framework 2.0.

Interprofessional Competencies

As mentioned above, health IT as well as the treatment of patients is interprofessional by nature. There are always differences in the need for digital skills in the various health professions, yet there is also a large common overlap between the professions.

Professions working in direct patient care (such as physicians, nurses or therapists) share many common competencies such as documentation, quality management or information and knowledge management. Other professions such as IT engineers and chief information officers or IT engineers and executives also have a large overlap in their competencies. In particular, communication and leadership are of special importance to all occupational groups in healthcare in order to support interprofessional cooperation.

The aim is to integrate health informatics core competencies into the traditional training, curricula and courseware (at all educational levels) and to prepare the teachers as gatekeepers and multipliers in education. Finally, the common core competencies can also be used for collaborative education between the professional groups.

Aligning Core Health Informatics Competencies

By Marisa L. Wilson, DNSc, MHSc, RN-BC, CPHIMS, FAMIA, FAAN, Associate Professor/ Interim Chair, University of Alabama at Birmingham; a HIMSS TIGER International Task Force Member

Our lives are spent interacting with technology and the data and information produced. The flow of our lives, both personal and professional, have been, and will continue to be, impacted by technology implementation. The changes that occur from the interactions of people, processes, technology and data can be supportive or destructive. Much of that divergence stems from how the technology and data are used. The move toward a supportive process requires users who are competent and ethical in the use of devices, information systems, data management and technology mediated interaction.

Banking, retail, communications, entertainment, education, and now healthcare, have all been transformed by technology implementations. What has not necessarily happened with the transformations, particularly in healthcare, is the positive optimization of those implementations. The healthcare organizational and operational changes needed to ensure technologies and data improve the interactions with patients and consumers has been diminished by often the lack of fully competent users. Full beneficial use requires proficient and competent point of care professionals. Moreover, healthcare systems are particularly risk adverse and the clinicians who interact with the patients and consumers require knowledgeable engagement in implementations to ensure minimal negative outcomes.

In addition, there is internal and external pressure for healthcare systems to improve and learn in order to make care more efficient, effective and satisfying all within the context of a technology rich environment. In order to accomplish these tasks and create that learning health system with the tools and processes available, healthcare students and current providers must be educated to utilize the tools to form data, information and knowledge to fuel the learning cycle within the system.

However, there is an issue. Healthcare providers often receive poor or nonexistent education in informatics and the use of information technology to advance care during their professional formation.

Competencies Needed

Nearly two decades ago, the Institute of Medicine produced five core competencies that all health professionals should possess regardless of discipline to meet the needs of the 21st century healthcare systems. They are:

- Apply quality improvement

- Employ evidence-based practice

- Provide patient centered care

- Utilize informatics

- Work in interdisciplinary teams

Each individual profession’s overseeing association has taken on the task of trying to lay out its professions expected informatics and IT competency set, to a more or less successful outcome. We will explore just three, starting with nursing which has the most defined list.

Nursing

The American Association of College of Nursing (AACN) took these competency expectations and incorporated them into the Essentials. In nursing education, expectations of nurse graduates at the bachelors, masters and doctoral levels delineate informatics and IT competent use as essentials. This set of essentials, however, date back to 2006 and are being re-envisioned to meet the needs of the industry today. Therefore, detailed specifics related to the measurable sub competencies will not be presented here.

However, what remains of these re-envisioned essentials will include informatics and IT as a key domain and a set of core competencies. Domain 8, Informatics and Healthcare Technologies, will contain actionable and measurable competency expectations for many graduates of U.S. nursing schools for which the school will be responsible to provide to the students. At this writing, the categories of competencies in Domain 8 fall into the following:

- Demonstrating the use of information and communication technologies and informatics processes to deliver safe nursing care to diverse populations in a variety of settings

- Understanding how the various information and communication technology tools used in the care of patients, communities, and populations

- Use information and communication technologies in accordance with ethical, legal, professional and regulatory standards, and workplace policies in the delivery of care

- Use information and communication technology to support chronicling of care and communication among providers, patients, and all system levels

Medicine

Physicians, like there nurse team members, will also need to interact competently with IT and informatics processes. Although no unified documentation on expected informatics competency for general medical education is available through the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC), the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) does lay out the program requirements for fellowship in clinical informatics for graduates of ACGME accredited programs as also outlined through the American Medical Informatics Association (AMIA). For all medical education, a group from Oregon Health & Science University did document specific learning objectives and milestones to support developing informatics competent medical practitioners. These competencies were developed through a consensus agreement between the group of six faculty.

The team offered multiple competencies across the continuum of medical education. Among them are:

- Apply personalized/precision medicine

- Engage in quality measurement selection and improvement

- Engage patients to improve their health and care delivery through the use of personal health records and patient portals

- Find, search and apply knowledge-based information to patient care

- Maintain professionalism through the use of information and technology tools

- Participate in practice-based research

- Protect patient privacy and security

- Provide clinical care via telemedicine

- Use and guide implementation of clinical decision support

- Use health information exchange (HIE) to identify and access patient information across settings

- Use information technology to improve patient safety

Pharmacy

As with other interprofessional team members, pharmacists are also expected to demonstrate competency using IT and informatics processes to impact better outcomes. However, going back nearly a decade, it was noted that the education provided for the student to achieve competence, despite inclusion in Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education Standards and Guidelines, as a requirement was found to be inconsistent. More recently, it appears that there is work to refine and revise those competencies.

The pharmacist informatics task force of the American Academy of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) used 11 sources and faculty feedback to create a revision. This revision lists the following domains with detailed, aligned competencies:

- Emerging Technologies

- Health Care and Clinical Biomedical Informatics

- Interoperability and Standardization

- Legal and Regulatory

- Patient Outcomes

- Practitioner Development and Education

A Gap

Those responsible for educating or training the students or current providers, despite mandates to do so, are themselves often lacking in knowledge, skills and attitudes so that there is not a transference of knowledge and skill that results in a demonstrable competency. As an example, the AACN reports that the average age of nursing faculty with a doctoral degree for positions of professor, associate professor and assistant professor were 62.4, 57.2, and 51.2 years.

These faculty members were most likely not educated about informatics during their own time in school and perhaps not even during clinical practices. This results in an informatics skill and competency gap among graduates. For nursing, this significant gap has been identified by the HIMSS TIGER (Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform) initiative, the European Commission’s EU*US eHealth Work Project, and the Nursing Knowledge Big Data Science Education Work Group.

Substantiating the Gap

To substantiate and justify the size of the gap, the EU*US Work Project Consortium, funded by the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 innovation grant program, issued a survey to over 1,000 targeted respondents to measure the need, supply and trends that support necessary workforce skills and competencies. Over 1,000 responses were returned from 51 countries around the world. Respondents represented all of the healthcare professions involved in health IT and represented the full spectrum of the healthcare workforce.

A synthesis of results pointed to several major gaps related to training and skills, the top four address:

- Availability of courses and programs

- Lack of knowledge and skills of faculty and educators

- Lack of knowledge and skills of providers and caregivers

- Quality and quantity of training materials. Moreover, research identified the pressure placed on universities to deliver eHealth education in a curriculum wide approach for which the universities are struggling to meet the needs for applicable and novel learning opportunities.

Ursula Hübner with the University of Applied Sciences Osnabrück and Beth Elias with University of Scranton with TIGER share the strategic approaches to seamlessly delivering health informatics education HIMSS TV.

A Solution and Resources

Given the serious need to have health professionals and graduating health professional students competent in the provision of quality and safe care using IT and informatics processes, faculty and educators providing the knowledge, skills and attitudes on the topics must themselves be competent. Moreover, given that there are not enough health professionals with formal informatics education and training to take on this challenge, support must be provided to those who currently interact with the profession and the students.

TIGER International Competency Synthesis Project

The TIGER International Competency Synthesis Project’s Global Health Informatics Competency Recommendation Frameworks provide a comprehensive and compiled core set of international and interprofessional informatics competencies for nursing and other healthcare professionals.

Framework 1.0 is nursing centric and lays out two sets of core competency tables. In the first grouping, there are expected nursing informatics competencies that align with direct patient care, quality management, coordination, management and IT roles a nurse may hold. These competencies align with the AACN Essentials including the re-envisioned version. The second, more expanded set, align with all health professions across multiple levels. This expanded set contains four domains under which multiple competencies align:

- Biostatistics and technology

- Data, information and knowledge

- Information exchange and information sharing

- Management in informatics

Resources

As stated previously, despite all of this competency work and the expectations across various health professions, there is a significant gap. The gap is exacerbated by the knowledge, skills and attitudes of those currently teaching and educating. So, rigorous support and guidance has to be provided to those educators and faculty. There are tools to help, including the following.

Global Health Informatics Competency Recommendation Framework 1.0 (nursing) + 2.0 (interprofessional): This describes the framework with all the domains and competencies. A review of this document will demonstrate an alignment with the core informatics expectations of the AACN, AAMC, ACGME and AAPC.

Health IT Competencies Tool & Repository (HITComp): This web-based tool that lets you explore specific competencies, sub competencies across roles and education. It is aligned with the Global Health Informatics Competency Frameworks and serves as a detailed companion guide.

Interactive Education Demonstrator Modules: These modules provide instructional videos on the foundational curriculum, HITComp and cybersecurity focused on targeted malware attacks.

Skills Knowledge and Assessment Development Framework (SKAD) is a questionnaire focused on self-assessment to better understand personal digital literacy skills.

Today, more than ever, there is a major need to improve the informatics competency and skills of not only of the healthcare workforce but of those who teach and guide them. These tools offer an opportunity to address the gap in both areas.

Workforce Development

By Hank Fanberg MBA, CPME, FHIMSS, Instructor, Digital Health and Informatics, the University of New Orleans; a HIMSS TIGER Member

Look at any position open announcement and you’ll find a section with the header of “qualifications,” “desired skills, knowledge and abilities,” or something similar. This is how an employer informs applicants of the skills and knowledge necessary to perform the responsibilities of the position. These are the competencies the employer seeks in individuals that apply for the job.

As noted above, a competency is the capability to apply or use a set of related knowledge, skills and abilities required to successfully perform critical work functions or tasks in a defined work setting. Competencies often serve as the basis for skill standards that specify the level of knowledge, skills and abilities required for success in the workplace, as well as potential measurement criteria for assessing competency attainment.

Just as companies seek to employ persons with skills and competencies in a given area, educators are also concerned with competencies. An educational institution would define competencies as “a general statement detailing the desired knowledge and skills of student graduating from a course or program.”

Is education strictly for intellectual development or to prep people for the workforce? One goal of education is to produce citizens who can think critically and have knowledge. A competent critical thinker may be necessary yet insufficient for being competent at work. Knowledge for knowledge’s sake is important. It is possible to learn many things and become well educated. This may not, however, readily translate into workplace competencies.

Demonstrating competency is not simply performing well on tests and other knowledge evaluation activities. It’s rooting out the core areas of knowledge a student must demonstrate for mastery, that they understand the material, have studied and applied the content to certain situations or learnings and that they have mastered the material and can now be called competent. These two forces—the competency needs of employers and the competency content of an educational course of study—should overlap, but they are different.

A competency demonstrates proficiency. Competency denotes “having the knowledge, skills and ability to perform or do a specific task, act or job (Mastrian & McGonagle, 13). Informatics competency would be the knowledge, skills and ability to perform specific informatics tasks. A number of national and international groups work to identify core informatics competencies. Competencies are not just a one-time thing. They are continually evaluated in the field and by educators. Each sector has its version of competencies and include:

- Academic competencies

- Industry-wide competencies

- Management competencies

- Personal effectiveness competencies

- Workplace competencies

We can see that academic/educational competencies are separate from workplace competencies. Yet the two must work in tandem, each informing the other so that education enables competencies when one transitions from education to the workforce. They form a feedback loop and as innovative processes and advances are adopted in the work environment; the academic arena must adapt its competency model to fulfill the ever-changing competency needs of employers. This is absolutely true for health informatics. They are yin and yang; one cannot do without the other.

A Multidisciplinary Field

Informatics uses data to solve all manner of problems—little problems such as the best way to stack items in a truck to bigger issues like tracking COVID-19 to see who has been exposed and who has not. The common element is data—its collection, its aggregation and its sorting into meaningful, useful information.

This multidisciplinary field exists at the intersection of healthcare, information science, computer science and technology. Health Informatics is "the interdisciplinary study of the design, development, adoption and application of IT-based innovations in healthcare services delivery, management and planning. It also involves using health information systems in collecting, storing, retrieving, analyzing and utilizing healthcare information for a variety of purposes. It requires that the health informaticist be proficient in the language of health and healthcare, health IT tools and standards, systems design, project management, human factors and perhaps most importantly, collaboration with all the medical professionals, administrators and others that rely upon health information and technology in performing their duties and responsibilities. Critical thinking and communication skills are just as important as the other skills for the health informaticist. The health informaticist focuses on the end users and tailoring systems to satisfy their needs.

Before the computer era, medical science relied upon the basic sciences and the bench scientists—biology, chemistry, anatomy, physiology and others—to advance knowledge. The addition of computer science and data science to the practice of medicine gave the healer clinical decision-support tools new ways to record their patient interactions, and provide on-demand access to their professional body of knowledge. Researchers had access to data faster and more accurately than ever before.

The Health Information Technology Advisory Committee Act within the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 provided funding for doctors and hospitals to adopt electronic medical records in the U.S. Recently we’ve seen more than 85% of physicians and more than 95% of hospitals use an EMR.

Now we have the tools to better support practitioners’ responsibilities such as finding all the diabetic patients in the practice who have not had an A1C test in the past three months versus having to search through paper records until they found those patients. This one simple example demonstrates how informatics impacts the quality and outcomes of medicine. And it is the health informaticist who plays a critical role in the design, delivery and experience of the end user.

As computational power and capability continues to grow, and as the collection, assemblage and analysis of data becomes more necessary, the world of health informatics opens up, and its needs from the workplace then form a feedback loop with education.

Demand for Health Informaticists

According to the U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics, health informatics will experience a 22% job growth between 2012 and 2022. The salary for these positions exceeds $100,000. Variety and opportunity are vast for those interested in pursuing a career in the field. Keep in mind that many of these jobs require skills from different disciplines. Many of these positions remain open longer than the average meaning that opportunities abound for the well prepared.

Health Informatics Branches

The field has many branches. There are multiple paths to follow, including that of data scientist (although data science is considered a related and overlapping discipline). The need for competent health informaticists and data scientists is growing exponentially. Additionally, the amount of data produced by the healthcare industry is expected to grow exponentially, creating opportunities aplenty in the following areas and others:

- Clinical Informatics

- Consumer Health Informatics

- Nursing Informatics

- Pharmacy Informatics

- Public Health Informatics

1. Clinical Informatics

Professionals working in clinical informatics use data to support clinical decision making. A clinical informaticist may serve in a multitude of roles, depending on the size of the healthcare setting.

2. Consumer Health Informatics

Consumer health informatics roles involve protecting consumer health.

3. Nursing Informatics

The American Nurses Association defines the position as overseeing the integration of data, information and knowledge to support decision-making by patients and their healthcare providers. Nurses with technological skills may want to consider looking for a job in this field. While the Bureau of Labor Statistics does not track nurse informaticists specifically, the demand for computer systems analysts—a role with comparable skills—is expected to grow faster than other occupations over the next few years.

4. Pharmacy Informatics

Pharmacy informatics involves using data in the process of supplying medication. Demand for pharmacy informatics is growing rapidly due to the wide spread use of electronic prescribing and EMRs.

5. Public Health Informatics

Public health informaticists concern themselves with the health of populations. Some people in this field prepare for threats such as antibiotic resistant infections and biological attacks. Public health informatics jobs are found in hospitals, government agencies or private businesses.

Healthcare has always been data driven. As more and more data are created the need for health informaticists with the mix of proficiencies in communication, computer science and clinical capabilities will be in great demand for years to come. Using data and computer systems has the huge potential for improving quality, improving the user experience and lowering costs and is one of the few areas in healthcare where providers, insurers and policymakers of both parties agree. This is also one of the areas of consistent job growth. The opportunities are there. Now go after those proficiencies.

The views and opinions expressed in this content or by commenters are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of HIMSS or its affiliates.